FRANCE WAS NOT A UNIFIED COUNTRY AT the end of the 12th century. In 1180, Philip II ascended its throne and was the fi rst to style him- self “King of France” rather than “King of the Franks.” He achieved control over much of northern France through warfare and diplomacy, earning the nickname “Augustus.” Even so, the rest of the country remained a collec- tion of duchies and counties whose rulers behaved like independent monarchs. In the south, the people did not even speak the same form of French; instead, they spoke a dialect known as Occitan (or Languedoc). Th e dominant barons in the Languedoc region were the counts of Toulouse, first appointed to rule the region by Frankish King Louis the Pious in 788. As that realm declined in the 9th century, the Toulouse barons declared their independence. It was under those circumstances the Cathars appeared and fl ourished across Languedoc by the mid-12th century, with their greatest concentration in the counties of Toulouse, Foix and Carcassonne. Among the nobility at all levels, both in towns and castles in the countryside, Catharism thrived as an expression of independence and the unsettled relationship with Roman Catholic authority. Derived from the Greek katharos (meaning “pure”), Cathar theology drew heavily on the early doctrines of the Byzantine Balkans. Th ey embraced Christian themes and parts of the Gospels, but they openly rejected the author- ity of Roman Catholic clergy, including the pope, as cor- rupted and unworthy. Th ey also neglected to pay tithes. By the 1170s, the sect had self-organized into dioceses with their own bishops and deacons who acted as parish priests. Th ere were also wander- ing men and women, known as “perfects,” who preached and administered “purification.” That was Catharism’s only sacrament, and it consisted of the transmission of the Holy Spirit through the laying on of hands by perfects to those close to death. Perfects took vows of chastity and poverty and lived austere lives, including fasting and abstaining from meat and eggs.

A portion of the towers and walls of the citadel of Carcassonne. Shutterstock Photo.

Th e existence of Catharism in Languedoc was well-known in the Vatican by the mid-11th century. Eight church councils condemned them between 1022 and 1163, the last of which declared Cathars were “to be shunned, outlawed, sought out by the authorities and arrested.” After the Third Lateran Council approved military action against them in 1179, Cardinal Henry of Marcy led an army into Languedoc and threatened Lavaur castle. After the garrison submit- ted peacefully and two excommunicated Cathar bishops publicly recanted and returned to regular Catholicism, the campaign ended without bloodshed. By 1200, Languedoc was home to over 1,000 perfects and a much larger number of lay believers. The latter were not expected to adhere to the strict lifestyles of the perfects, but they were called on to support their local churches fi nancially and materially. In return, they were guaranteed to receive the rite of purification prior to their death.

Elevated to the papacy in 1198, Innocent III sent delegations of friars to Languedoc over six years to preach the gospel and peacefully convert Cathars. However, they met with little success. In January 1208, with Count Raymond VI of Toulouse unwilling to assist the legates, Pope Innocent III excommunicated him and declared the Albigensian Crusade. Among other things, that forbade persons living with- in them from receiving Christian burials. Raymond reacted by conferring with legate Peter de Castelnau. Though the two exchanged harsh words and threats during their talk, Raymond swore to comply with all the pope’s demands, hoping to have his excom- munication lifted. However, the next day, as de Castelnau and his retinue were about to cross the Rhone River, a man-at-arms fatally struck the legate and then fled on horseback. Raymond denied involvement, but Innocent III concluded a stronger approach against the heresy was needed.

Convinced the Cathars posed a threat to the church, in March, Innocent issued a call for a crusade against Raymond, all heretics in Toulouse and Languedoc and all those who sustained them. Th e cru- sade would begin in June, and those who served 40 days or more would receive the same indulgence—remission of past sins—given to those who crusaded in the Holy Land. The pope gave overall command to Arnaud Amaury, Abbot of the Cistercian monastery at Citeaux. Named for the town of Albi, home of the fi rst Cathar diocese, the “Albigensian Crusade” was unprecedented. It was the fi rst time a pope called for holy war against Europeans who consid- ered themselves Christians rather than against pagans or Muslims. Attracting northern nobility who were eager to obtain land and indul- gences, the Crusader army assembled at Lyon in June 1209. Among Amaury’s recruits were Duke Odo III of Burgundy and Count Herve IV of Donzy. They had each been allowed by their over-

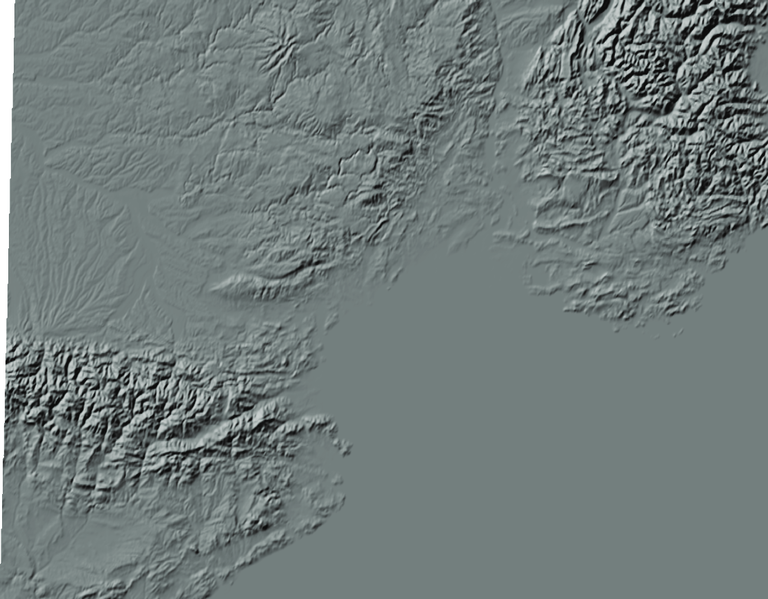

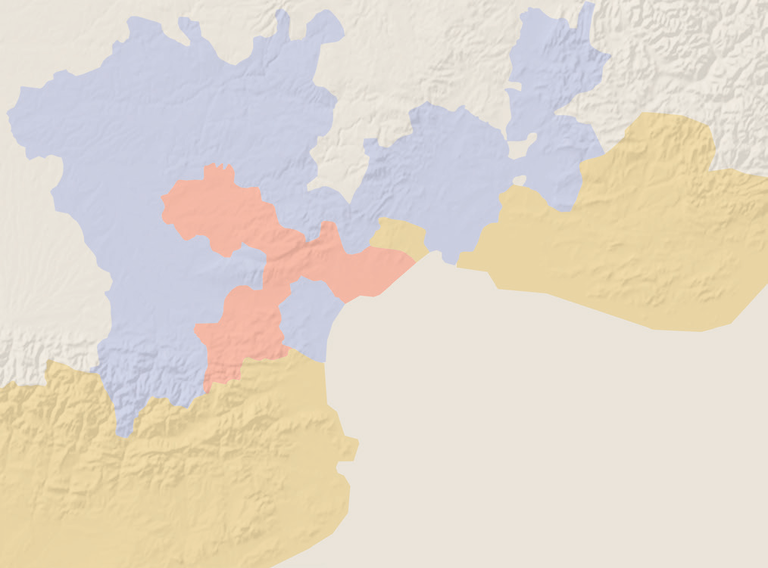

The Albigensian Crusade

Cère

1209–1229

Lot

A v e y r o n Rodez

Gard

Tarn

lord Philip to take 500 knights on the crusade. One of Odo’s men was Simon de Montfort, the Earl of Leicester, a veteran crusader and ruthless warrior. The Crusader army, numbering over 10,000 combatants and camp followers, departed Lyon and moved down the Rhone Valley into Raymond’s lands. As they approached Toulouse, Raymond again appealed to the pope for absolution. After he was publicly scourged, confessed his sins and swore to cor- rect his transgressions, the pope lifted Raymond’s excommunication on 18 June. He then joined the crusade to keep his lands and castles from being attacked after he switched sides. “The count was a false and faithless crusader. He took the cross not to avenge the wrong done to the crucifix, but to conceal and cover his wickedness,” wrote contemporary chronicler Peter des Vaux-de-Cernay. The Crusaders therefore marched instead for the lands of Raymond- Roger Trencavel, viscount of Albi and Béziers and Raymond VI’s nephew. Raymond-Roger swore loyalty to the Catholic Church and attempted to negotiate with Amaury but was rebuffed. He then hurried to Carcassonne to command its defense. The Crusaders arrived at Béziers on 21 July. That city’s Catholic bishop pleaded with the populace to either surrender all suspected heretics or save themselves by fleeing. Despite that, most of the townspeople chose neither to leave nor surrender their friends and neighbors. Hostilities erupted the next day when some armed civilians sortied and attacked a group of Crusader camp followers. Aided by some soldiers, the ill- armed camp followers gained the upper hand and chased the citizens back into the castle. Observing the melee, Amaury sent forward his entire army, and Béziers fell in a few hours. After its capture, Amaury and his knights confiscated all the spoils, after which the angry camp follow- ers set the city ablaze. The Crusaders killed the entire population of 8,000—Cathar and Catholic alike. With the castle overflowing with refugees, Raymond Roger surrendered Carcassonne in mid-August after the

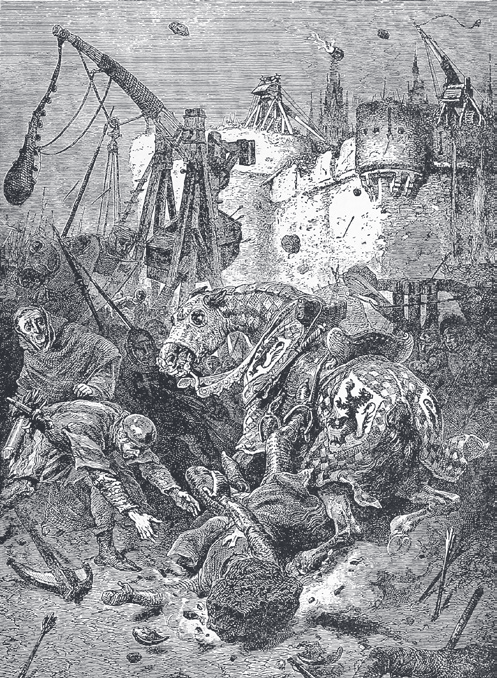

Crusaders cut off its water supply. He was imprisoned in his own dun- geon, where he died within months. Further, the populace was expelled from the city with nothing more than the clothes on their backs, after which the Crusaders looted the town. In need of a military commander and ruler for the Trencavel lands, a panel of clergy and nobles chose Simon de Montfort for both posts. During the autumn, Albi, Castelnaudary, Castres, Limoux and Montreal all fell, while an attack on the castle at Cabaret in Lastours was repulsed, ending hostili- ties for the winter. Appalled by the car- nage, Raymond VI abandoned the cru- sade and returned to Toulouse, where- upon he was again excommunicated. After more recruits arrived in the spring of 1210, Montfort swept through the Minervois region in March, pillaging and burning the lands of anyone who questioned his authority. His siege of Minerve ended on 22 July when the town surrendered after running out of water. After the garrison and lay Cathars were allowed to leave, the perfects were offered the choice of conversion or death. After just three converted, the 140 who refused were burned in a great pyre, many of them by rushing into the flames. Montfort attacked the castle of Termes in August, using sappers and trebuchets to weaken its walls. Fearing a massacre, the entire male population fled, leaving behind Lord Raymond of Termes and all the women. Surprisingly, Montfort chose to treat them well and ceased operations there for the winter. In April, Montfort besieged Lavaur. During that siege, troops under Count Raymond-Roger of Foix, backed by local peasants, ambushed and wiped out some 1,500 German Crusaders in the forest of Montgey as they marched to join Montfort. In retaliation, when the town fell on 3 May, the Crusaders hanged its 80-man garrison. They followed that with the burning of about 400 Cathars who refused the offer to convert. They also threw one of Aimery’s sisters screaming into a well, killing her by throwing rocks down on her. After capturing Casses and Montferrand, the Crusaders began

Carcassonne in 1209, from Grandes Chroniques BELOW: The expulsion of the inhabitants from de France, c.1415.

the first siege of Toulouse. (Some of Raymond VI’s men had fought at Lavaur, thereby providing Montfort justification to attack his lands.) However, running low on supplies and vastly outnumbered by the city’s 35,000 inhabitants, Montfort had to withdraw after a few weeks. Emboldened, Raymond VI went on the offensive with 2,000 troops, besieg- ing Montfort and some 500 soldiers in Castelnaudary. Rather than fully block- ade the town, the inept Raymond merely set up a fortified camp nearby, which allowed the defenders to receive regular deliveries of food and other supplies. When Count of Foix Raymond- Roger engaged a column of reinforce- ments heading to Castelnaudary, Montfort rode out with 60 knights and turned that looming defeat into a victory. Raymond VI, who had remained in camp during the fight, lost heart and withdrew to Toulouse.

Montfort campaigned across Languedoc in 1212, subduing the coun- ties surrounding Toulouse and raiding the lands of Raymond VI. By the end of the year, much of the countryside was in his hands. However, the major cities, including Toulouse, held out. By that time, Montfort had in eff ect built a large holding of his own from confi scated territories. He governed much of southern France and had even begun grant- ing land to some of his followers. Crowned King of Aragon in 1205 by Innocent III, Peter II was a hero of the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa, fought in July 1212, a milestone in the Spanish Reconquista . He had stayed out of the fighting in Languedoc through the fi rst half of 1213, but when neither the pope nor his legates would rein in Montfort, he felt he had no option but to take up arms to aid his vassal and brother-in-law, Raymond VI. Th ough the pope threatened him with excommunication, Peter fought a pitched battle against Montfort’s forces at Muret on 12 September. Though heavily outnumbered, Montfort’s superior battlefi eld skills won him the day. Peter and many of his nobles were

killed, and his army routed with heavy losses. With that, Raymond VI and his son Raymond VII fl ed to England. After invading the county of Perigord and capturing a number of castles, including Castelnaudary, Montfort and his Crusaders entered Toulouse for the first time on 15 May 1215. Six months later, the Fourth Lateran Council officially proclaimed him the Count of Toulouse and Duke of Narbonne, after which he submitted to Philip as his overlord. That arrangement was unpopular among most southerners, so Raymond VI and his son returned in April 1216 to reignite the resistance. Raymond VII led a successful three- month siege of Beaucaire, repulsing all attempts by Montfort, his brother Guy, his son Amaury, and the Crusader army to relieve the city. Hearing reports that Toulouse was about to rebel, Montfort hur- ried there and partially sacked the town, demanding oaths of fealty from the citi- zens and imposing a huge cash indemnity that further alienated the townspeople. Innocent III died unexpectedly in July and was succeeded by Honorius III. Th e new pope opted to continue the crusade and also began plan- ning a new one to the Holy Land.

In September 1217, with Montfort dealing with unrest in the county of Foix, Raymond VI, Raymond VII and a force of dispossessed nobles and their retinues entered Toulouse and regained control there without a fight. With that, the townspeople erected new fortifi cations. Montfort, by then running short on manpower and money, had no option but to wait out the winter. Urged on by Honorius, Montfort resumed the siege of Toulouse in the spring of 1218. He made no progress, and the siege dragged into its ninth month. On 25 June, while battling defenders who had sortied to attack a Crusader siege tower, Montfort was struck on the head and killed by a stone fi red from one of the castle’s trebuchets. Command passed to his son, Amaury Montfort VI de Montfort, who aban- doned the siege on 25 July and withdrew. Implored by Honorius to assume command of the crusade, King Philip again declined. Instead, he appointed his son, Prince Louis “The Lion,” to lead an expedition south in 1219. In June, the Crusader army under Amaury Montfort allied with him to besiege Marmande on the Garonne River. After the city surrendered without a fight,

A scene from the 6 August 2010 historical reenactment of the 800th anniversary of the siege of Termes. Courtesy of G. Baro, Wikimedia.

King Peter II of Aragon was one of Christendom’s most renowned and respected monarchs. Despite objections from many of his own vassals, he had himself crowned king in Rome by Pope Innocent III in 1204, and he declared his kingdom a feudatory of the Holy See. That devotion earned him the nickname “Peter the Catholic.” That all changed, however, when he took his army into southwestern France in 1213 to intervene in the Albigensian Crusade on behalf of his vassal and brother-in-law Count Raymond VI. Though threatened with excommunication, Peter marched across the Pyrenees and arrived outside the fortified town of Muret on 10 September. He and his men were joined by militia from the region, increasing his total force to about 3,000 combatants. He established a fortified camp northwest of Muret for his cav- alry, and the militia set up camp to the northeast near the Garonne River. Barges on that river provided easy resupply from Toulouse. Peter did not encircle or besiege the city. Instead, he waited for the arrival of Simon de Montfort and the Crusader army, hop- ing to engage them on open ground. When Montfort arrived with a force numbering 900 cavalry and 700 infantry, Peter allowed him to enter Muret unmolested.

A scene from the Battle of Muret, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, c.1375–1380.

A large flat fi eld lay north and northwest of the town, bor- dered north and south by two tributary rivers, the Pesquies and the Louge. The Perramon Heights and the Sandrune River were to the west, and the Garonne formed the field’s eastern boundary. Leaving his infantry to protect the town and its castle, Montfort rode out on the morning of 12 September, deploying his cavalry in three lines. His half-brother, Guillaume II des Barres, commanded the first line. Lord Bouchard I of Marly led the second line and Montfort the third. Des Barres was a former Crusader and one of the greatest warriors of that time. He commanded one of King Philip II’s armies during the conquest of the Angevin Empire (1200–04), and he distin- guished himself at the Battles of Arsuf (1191) and Bouvines (1214). Peter also deployed in three ranks, with his right protected by the Sandrune and the left anchored near the Garonne. Raymond- Roger commanded his first rank while Peter led the second rank, and Raymond VI had the third. Peter kept his army stationary and awaited the Crusaders’ advance. On Montfort’s command, des Barres led the fi rst two lines of cavalry, some 600 horsemen, in a frontal assault. Montfort stood by with 300 knights in reserve. Des Barres’ attack struck Peter’s front line with great force and shattered it. He then pushed on to engage the second rank. Seeing des Barres had gained the upper hand, Montfort led his reserve against Peter’s right, catching those men by surprise. Then Peter was killed, and his army disintegrated and fled, being pursued by the Crusader cavalry. Meanwhile, an attack by the Toulousain militia stalled in front of the town. When they saw Montfort and his troops returning and learned Peter had been killed, they fl ed by way of the river barges, sustaining heavy casualties as they did so. Montfort’s bold tactics had cost Peter his life, along with those of almost 2,000 of his nobles and troops. Aragon’s overlord- ship north of the Pyrenees was finished. ◆

The Battle of Muret

12 September 1213

Montfort at the siege of Toulouse, LEFT: The Death of Simon de 25 June 1218, from an engraving published in 1883.

Coronation of Louis IX during the RIGHT: The death of Louis VIII and siege of Avignon, from the Grandes Chroniques de France, illustrated by Jean Fouquet, Tours, c.1455–60.

Louis shocked his troops by order- ing the execution of its 5,000 civilian inhabitants while sparing the garrison. Louis and Montfort next besieged Toulouse, but after six weeks Louis unexpectedly led his army home. That left Montfort unable to hold his territo- ries with his thinned army. Raymond VII then retook much of that territory, including Castelnaudary, after an eight- month siege (July 1220–March 1221). In 1222, the year he died—still excommunicated and refused a Christian burial—Raymond VI had regained almost all his lands due to the efforts of his son. The county of Foix regained its independence, while much of the Trencavel lands reverted to the control of Raymond-Roger III’s son. Philip II died in July 1223. In 1224, Montfort abandoned Carcassonne, ceding his remaining rights to French King Louis VIII (the former Prince Louis The Lion). Louis VIII was eager to exercise his full royal rights in Languedoc. To expe- dite that, he had the Council of Bourges excommunicate Raymond VII and make him the target of the revitalized crusade. Raymond-Roger II (“The Great”), the

new count of Foix, tried to negotiate a peace but was rebuffed by Louis. After taking the cross in January 1226, Louis marched south in June at the head of a massive army, taking Béziers, Carcassonne, Beaucaire and Marseille without a fight. However, the city of Avignon, a holding of Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II, refused to open its gates. A long and costly siege (10 June to 9 September) finally ended in a negotiat- ed surrender, with the city paying 6,000 marks and destroying its walls in return for no killing or looting taking place. Louis next moved to besiege Toulouse, but his army had suffered severe casualties at Avignon and he had to return to Paris to regroup. He became ill on the way and died in November, to be succeeded by his 12-year-old son Louis IX. The boy’s moth- er, Blanche of Castile, became queen- regent and continued the crusade under the leadership of Humbert V de Beaujeu. De Beaujeu conducted punish- ing campaigns in 1227 and 1228, laying waste to the countryside around Toulouse, burning fields and farms and butchering livestock. Without the manpower to effectively

intervene, Raymond VII could only watch from atop the castle walls. By 1229, he had no alternative but to surrender to Louis, and in April the Treaty of Meaux ended the Albigensian Crusade. Under its terms, Raymond VII acknowledged the authority of the French king, allowed the Church to pursue heretics in his lands, and ceded the Viscounty of Trencavel to Louis. He also had to agree to the marriage of his only daughter to Louis’ brother Alphonso, who would inherit Toulouse on Raymond’s death. (In the event, Raymond VII died in 1249 and, after Alphonso and Joan both died in 1271 without heirs, Toulouse passed to the French crown.) With the crusade’s military phase end- ed, Pope Gregory IX established an inqui- sition in 1233 to continue the eradication of heresy throughout southern France. In retaliation for the murder of two of those inquisitors in May 1242, the last Cathar stronghold, the fortress of Montsegur, fell after a 10-month siege that ended with the burning of over 200 perfects. The remaining Cathar adherents thereafter worshiped in secret while the inquisition continued. Inquisitor Robert

le Bougre earned a particularly grim rep- utation. In 1236, he burned 50 Cathars in Champagne and Flanders; in 1239, he burned 183 more in Montwimer. The majority of condemned Cathars were lay believers who recanted when faced with death. Punishments var- ied, but most frequently they were merely made to wear yellow crosses on their clothing as a sign of pen- ance. Others made pilgrimages, went on crusade or were scourged. Cathars who were slow to repent or relapsed suff ered imprisonment and the loss of their property, while those who refused to repent were burned. Many Cathars were condemned after their deaths and were exhumed and their corpses burned. Others fl ed to Aragon, which soon ceased to be a refuge, or to Italy, where they continued practicing their faith for decades. Bernard Gui, inquisitor of Toulouse from 1307 to 1323, mounted a fi nal eff ort to eradicate Catharism, and by 1350 all known adherents of the movement were believed to have been killed or converted. Th e crusade’s methods and effective- ness in eradicating heresy have long been debated, with some historians considering it an act of genocide. Th e violence and atrocities were due to the crusade being co-opted by unscrupulous nobles, undisciplined mobs and overzealous local bishops. Th e crusade’s political outcome was clear—southern France was annexed to the Capetian dynasty. That began a long period during which French kings were far and away the most powerful rulers in Europe, exceeding even the pope and Holy Roman Emperor in infl uence. ❖

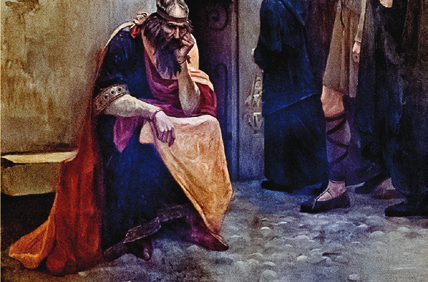

Count Raymond VI of Toulouse (r. 1195–1222) was a weak and callous ruler during the greatest crisis the region of Languedoc ever experienced, the Albigensian Crusade. Excommunicated several times, the period in 1208 was especially egregious, putting extraordinary pressure on his nobles and the people of his realm due to interdicts and an invasion by a Crusading army. When that Crusader army moved south from Lyon in June 1209, he was able to temporarily protect his lands, castles and vassals by repenting and taking the cross, getting his excommunication lifted, and joining the Crusader army. Having saved his own lands in that way, Raymond then convinced the Crusaders to invade the territory of his estranged nephew, Raymond Roger III de Trencavel, the Viscount of Albi, Beziers, Carcassonne and Razes. After Raymond Roger’s attempt to reconcile with Crusade leader Arnaud Amaury was refused, they invaded and looted his lands and massacred many of his people, both Cathar and Catholic. They imprisoned Raymond Roger in his own dungeon, where he died after three months. Raymond VI had meanwhile fled to England, only to be expelled from there on the pope’s order. He returned to Languedoc in February 1214. That spring, his half-brother Baldwin, who had supported the Albigensian Crusade from its onset, was captured by resistance fighters. After hearing that news, Raymond endorsed and then traveled to witness Baldwin’s execution by hanging for having participated in the Battle of Muret on the Crusader side. That disgraceful conduct further eroded Raymond’s reputation, earning him the nickname “the second Cain.” Raymond’s flawed judgment, his lack of competency in every level of warfare, and his inability to gain the trust of the nobles and commoners of his realm eventu- ally cost him his lands and titles. He abdicated in favor of his son Raymond VII in 1222, hoping to save his family lands from forfeiture. However, all of Languedoc came under the control of the French Crown a few decades later. ◆

Raymond VI, Count of Toulouse, the Excommunicated, painted by René-Henri Ravaut in 1889.

Selected Sources

Barber, Malcolm. in the Middle Ages. The Cathars: Christian Dualists Routledge, 2000. Chalk, Frank Robert & Kurt Jonassohn. and Sociology of Genocide: Analyses & Case The History Studies. Yale University Press, 1990. Costen, Michael D. Crusade. Manchester University Press, 1997. The Cathars and the Albigensian Falk, Avner. in the Crusades. Franks & Saracens: Reality & Fantasy Karnac Books, 2010. Tyerman, Christopher. of the Crusades. Harvard University Press, 2006. God’s War: A New History Wolff, Robert L. & Harry W. Hazard (eds). Crusades, 1189–1311. Press, 1969. University of Wisconsin The Later