The murder of Mary Bax

It’s the time of year for spooky stories – and this one is local and legendary. But what really happened?

Words & imagery courtesy of Sharon Powell

The modern road just off the ancient highway

As winter looms, the nights draw in and the traditions of Halloween begin, our thoughts turn to stories of the dark. The tale of a local woman attacked on a lonely road at the end of the 18th century by a wayward sailor is one that has been retold many times on a cold, dark night in front of a blazing fire.

The name Mary Bax is recognised by the many people in Deal who have stumbled across her memorial stone on the ancient highway towards Sandwich. And the crime has been written about many times, often with conflicting details. Some of these versions are more like works of fiction – all Victorian melodrama blended with local folklore. But, of course, there is a true story to be found among the differing versions, although it’s now impossible to prove definitively what that was.

When Victorian culture was at its height and the likes of Wilkie Collins published popular novels such as The Moonstone and The Woman in White, to sit alongside Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist and A Christmas Carol, the old tale of the murder of a young woman by a penniless sailor on a desolate highway must have really got the creative juices flowing. The story was already passing out of living memory, and so it began to transition from true crime to work of fiction.

The author Michael Ballantyne in his 1864 novel The Lifeboat has a murder taking place on “the bleak Sandhills” one evening, with Mary being accosted and then murdered by a “brutal foreign seaman” who had deserted his post. A similar work of fiction, Mary Bax: A Tale Founded on Fact, was written by Thomas Mills and published in 1850 by the Penny Illustrated News. It tells a similar tale, reminiscent of a torrid Victorian love story involving Mary and some hopeful young man hoping to win her hand.

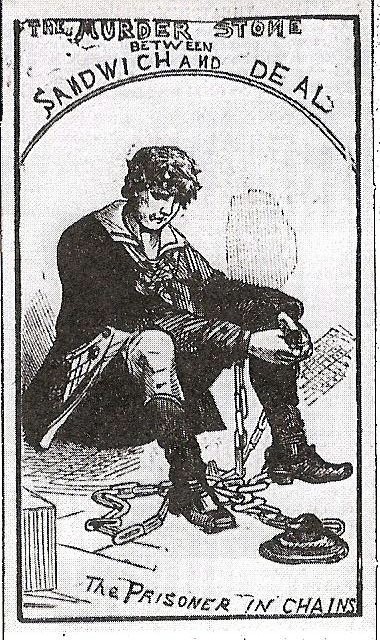

Clement William Scott also wrote about Mary’s death in his 1874 book Round About the Islands, or Sunny Spots Near Home in a piece dripping with exaggeration. But moving away from Victorian melodrama, embellishment and darkness, we have a parallel, believable story reported in the Illustrated Police News of 18 November 1882, almost a century after the murder. The article also carries a confession from the murderer.

From this, we can deduce that the day she was murdered – 25 August 1793 – Mary, who was 23 years old from a “respectable” home, was walking from Deal to Sandwich along the ancient highway. Today this road runs parallel with, and close to, the coastline between Deal and Sandwich, passing between farmland and Royal Cinque Ports Golf course. In the late 1700s it was known as the Sandhills and was rough and desolate, a mixture of pasture land and boggy marshes with streams and muddy dykes.

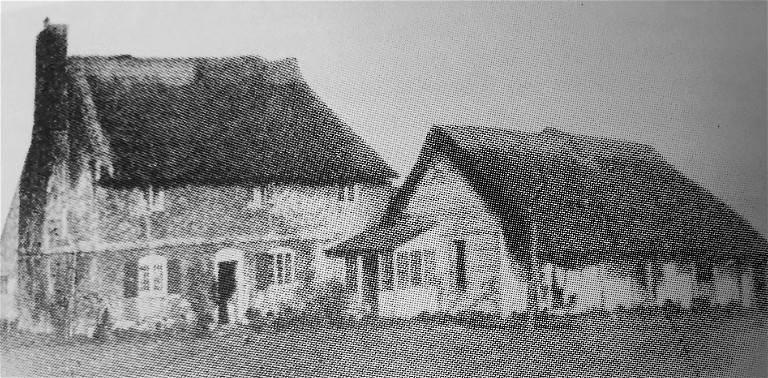

Mary’s brutal murder was witnessed by a shepherd’s son named Rogers, who was around eleven or twelve years old. There is an old picture showing a cottage in the area (see over) which had some foundations going back to the 17th century, so it’s possible that this could have been the cottage from where the young lad witnessed Mary’s murder.

As a witness in court, Rogers stated that Mary walked past him carrying a bundle or package and she had just passed the Halfway House (now known as the Chequers) when a man who was about 27 years of age, dressed in a white waistcoat and long stockings and carrying his boots under his arm, approached her and engaged her in conversation. This man was Martin Laas, who was born at Bergen, in Norway. He was a sea-faring man and came to England as a boy on a Danish trading ship. From there he joined the British fleet, and had served as an able seaman for several years.

Mary Bax’s “murder stone” on the site she was killed

Alater illustration of Mary’s murderer

In his later confession, Martin admitted to asking Mary for money and, when she didn’t give him as much as he wanted, he asked for her clothes. He then tried to strangle her but changed his mind, threw her into the nearby dyke and stood on her until she was dead. Wet and muddy, he made off across the marshes. The boy Rogers ran into Deal town and raised the alarm but, sadly, it was too late to save Mary and they focused their attention on finding her murderer. Having a good idea that he had gone in the direction of Dover, they put a watch on the town and soon found a man matching the description in a public house and arrested him. The report states that his conduct was “violent and rough in the extreme and he showed no compunction”.

He was taken away and committed to St Dunstan’s Gaol in Canterbury to await his trial at the next Maidstone Assizes. It appears Martin’s behaviour didn’t improve during his confinement and, at his trial on 20 March 1784, records show he seemed cheerful, mocked the court and insulted the witnesses.

In his own defence, Martin Laas could only say, “I was destined to commit the murder and I was told I should do it by an old Spanish sailor who foretold my destiny. I was destined to do it and was impelled to do it; therefore, I should not be hung.” This didn’t hold much sway with the judge and, when he announced the guilty verdict, Martin – undeterred – gave three loud cheers. On sentencing him to death by hanging, the judge ordered that, as his behaviour was so defiant, he should be chained to the floor in his cell.

It is reported that at his execution on Gallows Hill, Penenden Heath, just outside of Maidstone, he arrived, “quite willing to die and quickly mounted the ladder and in another moment or two paid the penalty for his crime”.

So what of poor Mary Bax? It is said that her friends and family raised the money for the memorial stone that stands where her murder took place and she is buried in a now unmarked grave in St Peter’s Churchyard, Sandwich. Herein lies yet another contradiction in this story, as the burial register shows the entry as 1783 but the stone and plaque say 1782.

It would be safer to go with the church burial record and the contemporary reports to ascertain the correct date, but this goes to show how, through the passage of time, local folklore, mistakes in documenting and works of fiction blending with fact, the truth behind the brutal murder of Mary Bax will always be clouded in mystery.

The old house near what is now the Chequers