NUTRITION

Getting spring ready

Equine nutritionist LARISSA BILSTON explains what

to expect from springtime pastures and offers tips

on keeping your horse safe from potential risks.

Days are getting longer and warmer, the soil is moist and spring grass growth has begun. For many, this is good news – plentiful grass means horses won’t need to be fed as much hay, and those who had trouble holding weight over winter will flourish.

But if your horse is an easy keeper, has a metabolic condition, or is prone to laminitis then the next couple of months require very careful management to maintain good health.

Spring also brings out bad or overly exuberant behaviour in some horses, often caused by excess calorie intake, high sugar intake and associated hindgut acidosis, mineral imbalance, changing levels of reproductive hormones and mycotoxin ingestion.

Weight gain & laminitis

Most pasture plants produce lush green growth during spring provided there is adequate rainfall. Horses consuming large volumes of these highly palatable pastures will gain weight and add to their fat stores. If your horse is overweight but not insulin resistant or dangerously obese, you may be able to achieve weight loss without removing them from pasture.

Obesity increases the likelihood of developing Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS), a condition that affects the body’s ability to use and store blood sugar, often leading to insulin resistance (IR). Note that some horses with Cushings also have IR.

By far the most common cause of pasture associated laminitis is a spike in blood insulin levels. This is triggered by eating grass, hay or hard feeds high in sugar and starch. During spring and autumn, pastures are naturally high in plant carbohydrates (sugars or starches), putting insulin resistant horses at high risk for laminitis.

When sugar levels increase suddenly, or the horse gorges on lush pasture, digestive upsets can occur as sugars that aren’t absorbed in the small intestine overflow into the hindgut where they are fermented by gut microbes. This produces more and different organic acids to those produced by fibre fermentation, which can cause gut pain, diarrhea, hindgut acidosis and dysbiosis (a change in the microbial population) any of which can affect behaviour and may lead to colic or laminitis.

Managing dietary ethanol-soluble carbohydrates (ESC) and starch is important for laminitis-prone horses even when they are not overweight. And if they’re insulin resistant due to EMS or Cushings then you need to be even more vigilant.

Obese horses, those with active laminitis and all horses with IR should avoid pastures with ryegrass and clover and usually need to be removed from all pasture during spring and autumn, or anytime that pasture plants are stressed. Grass can become stressed during drought or waterlogging, frost, herbicide application or severe nutrient depletion. Use yards or laneway systems without any grass, especially very short grass plants or runners and feed a controlled amount of ‘safe forage’ with salt and a concentrated mineral balancer.

Courtesy of Farmalogic

To encourage non-lame horses to move more, position multiple hay nets at opposite ends of the area to water. Laneway systems, especially those that create a loop, are particularly effective at encouraging exercise.

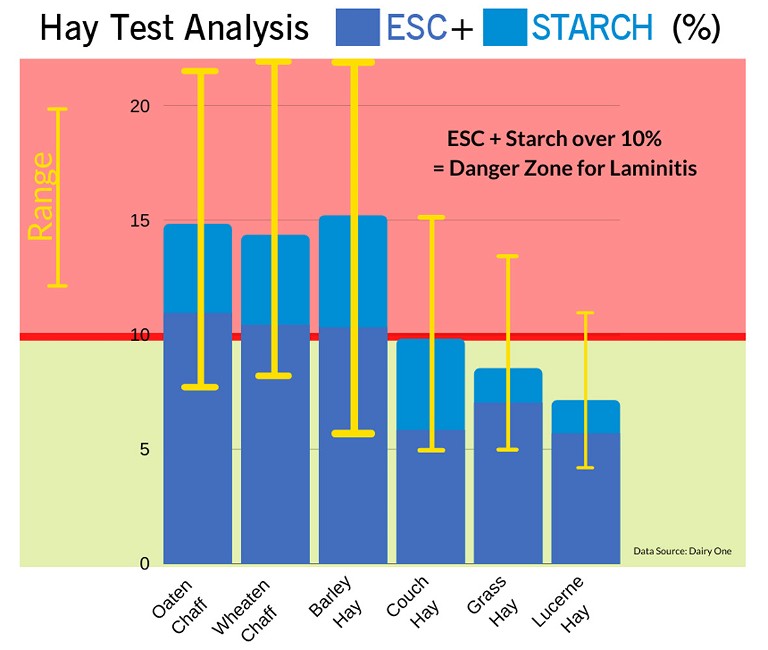

It is important to restrict intake to 1.25 to 1.5 per cent of bodyweight which equates to around 7kg of hay for a 500kg horse or 3.5kg for a 250kg pony. ‘Safe’ hay for IR horses and for weight loss is low in sugar and starch levels. Ideally, choose hay which has been analysed and has a combined ESC + starch value of less than 10 per cent.

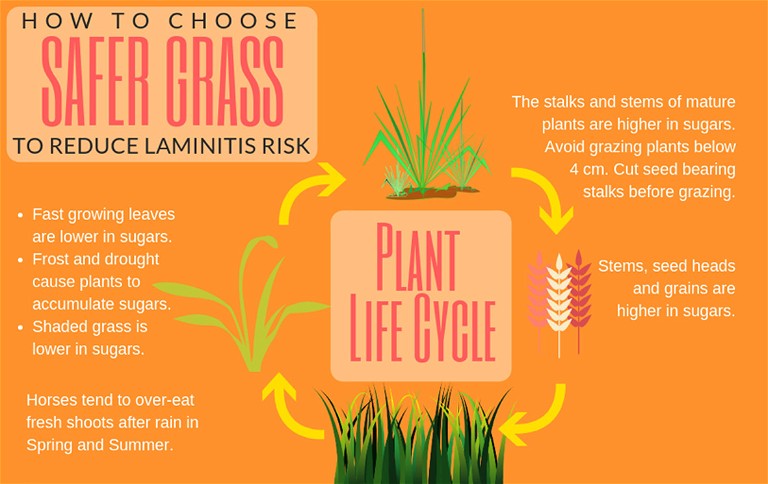

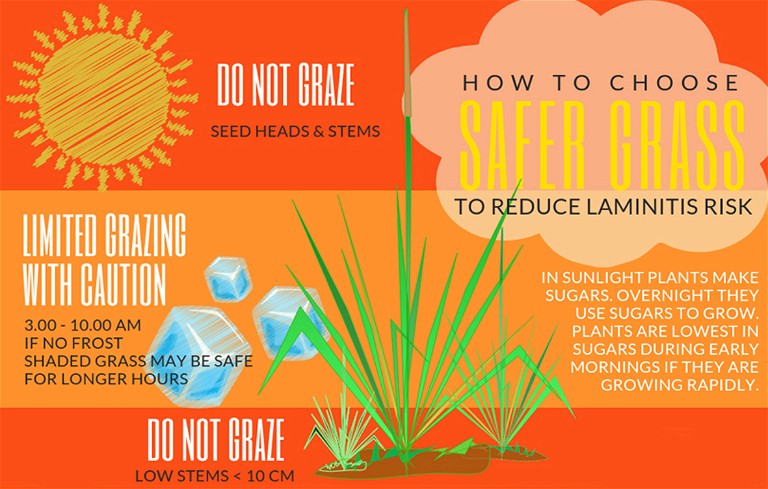

Although you can’t pick a suitable forage just by looking at it, the safest forages are rapidly growing, mid-length leafy grasses of native species or lower sugar introduced grasses. Avoid pastures or hay made from high production grasses such as clover and ryegrass and do not feed cereal (oaten, wheaten) hay or chaff. Limit lucerne hay to no more than 30 per cent of total daily intake. Do not give access to very short pastures (e.g. mowed or over-grazed) or grass carrying filled seed heads.

Courtesy of Farmalogic

The levels of starch and sugar become more concentrated later in the day as the sugars from photosynthesis accumulate. Stressed plants also accumulate carbohydrate as they experience slower growth. Although some plant species are more likely to be lower in starch and sugars, these levels change throughout the day, from day to day, week to week and across the season.

If carbohydrate levels of hay are unknown, soak in warm water for 30 minutes or cold water for 60 minutes to remove soluble sugars. Drain and discard soak water before feeding. Remove and discard any uneaten hay at least every 12 hours to avoid mycotoxin contamination. Soaking hay can reduce water soluble carbohydrates by 30 per cent but also removes some minerals, which need to be replaced with a quality, concentrated mineral balancer.

Provide a mineral supplement to top up and balance the levels in your horse's pasture. An overweight horse needs roughage, salt and minerals, but don’t feel that you have to give a ‘laminitis safe’ hard feed which, although low in sugar, is nevertheless adding calories that an overweight horse does not need. A handful of damp lucerne chaff, beet pulp or copra to act as a carrier for salt and a mineral balancer is all that’s required during weight loss.

Planting safer pastures

Successful long-term management of metabolic and easy-keeper horses can be improved by replanting with horse friendly lower sugar/starch pasture varieties:

In temperate zones

Choose a mix of slower growing, higher fibre, lower nutrient varieties such as Cocksfoot, Browntop Bentgrass, Yorkshire Fog, Crested Dogtail, or Prairie Grass. A good variety of Australian native grass seeds are now available but these plants aren’t always as resilient under hooved animals and heavy grazing as the introduced species. Look for Wallaby Grass, Native Wheatgrass, Native Bluegrass and Weeping Grass as these are amongst the best suited to grazing.

In tropical zones

Many tropical pasture grasses contain high levels of oxalates which bring their own challenges with managing horse calcium levels to avoid bighead disease. Rhodes is considered low oxalate, with under 5g oxalate/kg DM (dry matter), whilst Teff is considered moderate oxalate, falling in the 5-10g oxalate/kg DM range. High oxalate grasses such as setaria, buffel, para or signal grass contain 15-75g oxalate/kg DM.

Rhodes Grass is a high producing, low oxalate C4 grass preferred for planting horse friendly pastures in the tropics and subtropics, with Bluegrass, Native Wheatgrass, Mitchell Grass, Kangaroo and Wallaby Grass also well suited.

Macromineral balance

During spring and autumn, rapidly growing, heavily fertilised or stressed grass may become high in potassium and nitrate and low in sodium, which can have a dramatic effect on electrolyte balance and metabolism in horses, potentially leading to colic, grass-affected behaviour, grass tetany or grass staggers.

Manage overweight (but not IR) horses by:

• Removing excess calories from the diet by cutting hard feeds back to just a token amount to carry the necessary mineral supplements.

• Limiting the quantity of grass consumed with a grazing muzzle or by dividing the paddock into strips or small sections with moveable electric tape. Do not regraze sections until growth is at least 15cm high. If using a grazing muzzle, keep it on at least 90% of the time the horse is at pasture, to prevent compensatory gorging while muzzle is removed. (A horse can eat a full day's worth of food in just four hours!).

If your horse does not lose weight with these measures, lock your horse off pasture to give total control of the entire intake.